A Candidate of the Crowd

May 7, 2020 | Assistant Professor Martin L. Johnson

This is a blog post featured in the IAH Election Blog Series. The series aims to provide intellectual, humanistic and artistic insights on the 2020 U.S. elections. Faculty writers determine their own topic, looking to cover themes that foster conversations across differences and demonstrate the unique insights the humanities can offer. This blog post was written by Assistant Professor Martin L. Johnson in the Department of English & Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

A Candidate of the Crowd

In Elia Kazan’s 1957 film A Face In the Crowd, Andy Griffith stars as Larry “Lonesome” Rhodes, a singer and drifter who is discovered by a radio journalist (Patricia Neal) while reporting on a rural county jail. Rhodes’s folksy charm is a hit with radio audiences, and he soon auditions for a television show. Bristling at all the advertising copy he’s expected to read, Griffith turns his back on the studio audience, only to make sure that viewers at home can see him as he prefers—in front of a crowd.

Soon after Trump entered the presidential race in 2015, many writers have put forward Face as a film that anticipated the dangers of television populists. Like Trump, Griffith’s character has an intense bond with his audience, who is happy to support him even as he takes on increasingly bombastic political positions. In the film, Rhodes’s fortunes turn after a “hot mic” incident, in which Neal’s character decides to let the world know that Rhodes really sees his fans as dupes. Rhodes is exposed as just another grifter in an industry full of them.

But there’s another way to read Lonesome Rhodes’s downfall. As his fame grows, he becomes physically separated from his audience, and begins to see them as television producers do, so many points on a Nielsen ratings chart. Two of the film’s most compelling scenes come near the end. In the first, after the hot mic broadcast, but before Rhodes realizes what’s happened, a montage intercuts shots of Rhodes’s elevator descending to the ground floor with shots of angry television executives, the station’s busy telephone switchboard taking calls, and angry fans vowing to never watch the show again, as if to show how quickly mass appeal is undone. In the second, Rhodes is giving a fiery speech alone in his home, his butler turning on an applause machine at key moments to give him comfort. Removed from the crowd, and cut off from his audience, Rhodes has little left to live for.

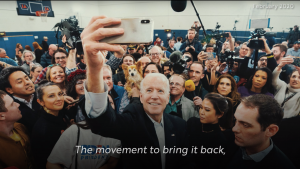

Since early March, the pandemic has meant that Donald Trump and Joe Biden are cut off from crowds. Like past presidents, Trump has always held a rally when he was looking to lift his spirits. While Biden’s presidential campaign has been comparatively quiet, even before coronavirus, Biden himself is known for his reliance on physical intimacy with his supporters. While we might debate whether politicians seek out crowds in order to achieve their own political objectives, or, as they often claim, to get in touch with ordinary citizens, the image of the crowd remains important to our perceptions of political campaigns.

At the same time, political and social theorists have long seen crowds as a threat to democracy. In 1895, the French social theorist Gustave Le Bon published his treatise, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, which argued that crowds were “impulsive and mobile,” unable to “admit that anything can come between its desire and the realization of its desire.” This skepticism of crowds runs through the 20th century, with politically charged mass gatherings seen as a potential threat to democratic institutions.

While fiction filmmakers have often presented the crowd as a threat, our politicians remain enamored with gatherings of supporters, perhaps because it helps them underscore their popular appeal. Three years after the release of A Face in the Crowd, the pioneering documentary filmmaker Robert Drew filmed Primary, a portrait of John F. Kennedy’s successful victory in the Wisconsin primary in April of 1960. Like Face, Primary tells the story of a candidate who draws life from the crowd. In the film’s most famous scene, a handheld camera follows Kennedy from backstage to a crowd of thousands, ready to hear him speak. We see Kennedy come to life in the presence of a crowd and become sullen and anxious in its absence.

We’ve already seen Trump and Biden adjust to life without crowds. Trump has taken to afternoon press conferences, with reporters replacing his supporters, often to unhappy results. Biden has started a podcast, an audio medium designed to reproduce the intimacy of a conversation. But neither is a substitute for a crowd. In fact, we only glimpse their preference for crowds in their campaign advertising. A Trump ad made in mid-March features a montage of images of his political rallies, almost all of them shots taken from the stage, with crowd noise underscoring his popularity. Likewise, a Biden ad released in late April also depicts the candidate in crowds, though all the shots are dated by month and year, as if to remind the viewer that social distancing rules were not yet in place.

In Donald Ritchie’s 1972 film The Candidate, Robert Redford stars as an accidental politician. Like Kazan and Drew, Ritchie uses scenes of crowds to underscore Redford’s popular appeal, and comparatively empty spaces to emphasize Redford’s personal doubts. The most famous scene in the film occurs near its end. After learning that he won his longshot bid for the U.S. Senate, Redford makes his way through a phalanx of supporters in order to take his political consultant (Peter Boyle) to an empty hotel room. Once there, he asks one question—“What do we do now?” Without crowds, it appears as if both Trump and Biden are asking the same thing.

If you are a UNC faculty member and interested in submitting a proposal for the series, please email IAH Communications Specialist Sophia Ramos at sophiav@email.unc.edu.